No Kathleen Valley stope this month – Liontown

The firm is aiming to shift to underground production next month, and maintains everything is on schedule

Recent announcements by some of the country’s largest e-mobility players are cause for optimism

It could be argued that India and the UK, the two locations Tata Motors has chosen for its planned first gigafactories, face similar challenges in the e-mobility revolution. Both have material, if not world-scale, domestic automaking sectors they want to futureproof with battery-making capacity.

And both are competing to build out battery supply chains with 1,000lb gorillas, in the form of the US and EU, in the race to close the gap on China and reduce reliance on the market leader’s current domination of certain links in the chain. India and the UK too have to walk a political tightrope between trying to benefit from the Chinese technological lead but establishing a supply chain at the lowest possible risk of being choked off by a potentially openly hostile Beijing.

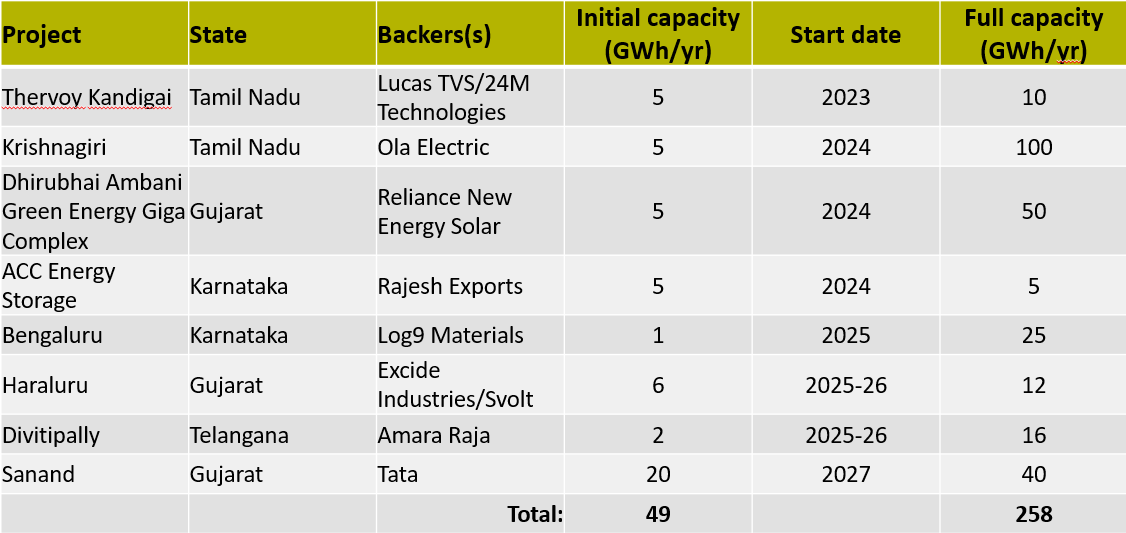

But there are also notable differences between the two countries. For one thing, Tata’s planned 40GWh/yr gigafactory in the UK is, barring another small project in Sunderland, northeast England, currently the only show in town in the UK. In contrast, the initial 20GWh/yr, with a potential doubling in a second phase, project Tata committed to in Sanand, Gujarat in June is one of at least eight projects in the works in India.

Not all may come to fruition, particularly given the aforementioned global supply chain challenges. But the announcements by Tata and by fellow Indian OEM Ola Electric, a specialist in two- and three-wheel vehicles, that it had broken ground on its initial 5GWh/yr gigafactory in Krishnagiri, Tamil Nadu inspire confidence that observable progress will be made.

Exciting times

The next few years promise to be interesting for Indian battery capacity. A first gigafactory, at Thervoy Kandigai, Tamil Nadu, is in theory scheduled to arrive before the end of 2023, according to the initial schedule laid out by its developer, Indian electrical components manufacturer Lucas TVS, when it signed a license and services agreement to construct the plant in September 2021. But there have been scant updates on the project since, which puts its delivery on that timescale significantly in doubt.

Much more likely to arrive in a timely manner are the gigafactory projects being pursued by Ola, by the new energy arm of Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries and by gold firm Rajesh Exports, as these projects have received grants from the Indian government’s performance linked incentives (PLI) scheme for advanced chemistry cell manufacturing. Part of the strings attached to PLI funding is a window for starting production, hence why all three projects are expecting to arrive next year.

There are at least three other Indian gigafactory projects are various stages of gestation which, if all delivered their initial capacity on their last-updated timeframes for start-up, could add up to 49GWh of annual capacity by 2027 (see Fig.1). But all but one of them have also outlined plans to grow their projects further, from doubling of some smaller projects to Ola’s vast ambition of scaling its initial 5GWh/yr up to 100GWh/yr.

Again, there are significant question marks about delivering on all these ambitions, but they add up to 258GWh/yr in total. That may seem a pretty large number, but possibly not particularly outsized in comparison to India’s growing battery needs.

Analysis last year by NITI Aayog, an Indian government public policy thinktank, put the country’s 2030 battery demand at anywhere between 50GWh in a conservative scenario to 130GWh in an accelerated scenario. Indian battery firm Excide Industries, which is developing its own gigafactory project in Haraluru, Gujarat puts it in the middle of those forecasts at 89.5GWh, split between 68GWh for e-mobility and 21.5GWh for industrial use.

By these measures, India is going to need at least a material portion, if not all, of its planned gigafactory projects and expansions to come to fruition if it wants to meet future demand through domestic production.

And other projects could yet emerge. Elon Musk, CEO of US OEM Tesla, has made no secret of his openness to take his firm into the Indian e-mobility market, which could well involve a new domestic battery facility. There are also murmurings that South Korean battery heavyweight Panasonic might be interested in pitching for some outstanding PLI funding from which its compatriot OEM Hyundai walked away.

Insider Focus LTD (Company #14789403)